A Working Capital Hub Fact Sheet

Working Capital and the Cash Conversion Cycle | Definition, Calculation and Considerations

Author: Alexander Flach

Last updated: August 13, 2025

Want to download this article for free?

Create a free account to download the article today.

Introduction

This article explains the Cash Conversion Cycle (CCC) - what it is, how it works, and why it is a critical measure of financial health.

The CCC shows how quickly a company can convert its investments in Operating Working Capital (OWC) - receivables, payables, and inventory – into actual cash.

Understanding this cycle is essential, because capital tied up in operations directly impacts the balance sheet and determines the amount of cashflow available to fund growth, pay debt, or build resilience.

Finally, the article explores why there is no universal definition of a “good” or “bad” cash conversion cycle. Instead, performance depends on the industry context and the company’s supply chain design, which shape what level of working capital is realistic and sustainable.

Strong profits don’t guarantee liquidity – the Cash Conversion Cycle reveals how effectively your business turns working capital into cash.

Key Take Aways

- The cash conversion cycle (CCC) metric looks at how effective a company is in managing its operating working capital.

- The shorter the cycle, the quicker it can convert its invested operating capital into cash.

- The CCC encapsulates three key stages of a company's operating cycle:

- the selling of current inventories,

- the collection of cash from current sales,

- and the payment to vendors for goods and services purchased.

- The CCC is calculated as Days Inventory Outstanding (DIO) + Days Sales Outstanding (DSO) - Days Payable Outstanding (DPO).

- The cash conversion cycle is measured in days and should be evaluated against a company's optimal level of operating working capital, its trend, as well as in comparison with relevant industry peers.

- CCC will differ by industry sector based on the nature of business operations.

What is the Cash Conversion Cycle?

The Cash Conversion Cycle (CCC) - also known as the Operating Working Capital Cycle or the Funding Gap - measures the number of days a company's cash is tied up in Operating Working Capital (OWC) before it is converted back into cash.

In practice, it tracks three critical timeframes:

- Inventory Days (DIO): How long it takes to sell stock.

- Receivables Days (DSO): How long it takes to collect payments from customers.

- Payables Days (DPO): How long the company can defer payments to suppliers without penalties.

The CCC combines these components into a single metric that shows how efficiently a company manages its working capital cycle.

A shorter CCC means cash is released faster, improving liquidity; a longer CCC means more cash is locked in operations, reducing flexibility.

How Can Cash be Tied up in Operations?

When discussing how cash can be tied up in operations, it's important to understand the concept of operating working capital.

Operating working capital refers to the funds a company requires and must finance to support its day-to-day operations, including the procurement of raw materials, production processes, inventory management, and invoicing & collection.

Cash becomes tied up in operations primarily due to the time lag between various stages of the purchasing, production, and sales cycle. Let's break down these core processes:

- Procurement of materials: When a company purchases raw materials from suppliers, cash is tied up in inventory. This cash is essentially locked into the form of materials until they are processed into finished goods and ready to be sold.

- Production processes: Once raw materials are acquired, they undergo processing and manufacturing, during which additional cash is invested in labor, equipment, utilities, and other overhead costs. This capital remains tied up in the form of work-in-progress inventory until the goods are completed.

- Inventory holding: After production, finished goods are held in inventory until they are sold to customers. During this time, cash is tied up in the form of finished goods inventory, which cannot be readily converted back into cash until a sale occurs.

- Sales and Collection: Upon selling the finished goods, the company generates revenue. However, cash may still be tied up in the form of accounts receivable, as customers often require time to pay their invoices. The longer the payment terms or the slower the collection process, the more cash remains tied up in accounts receivable.

Overall, the entire cycle from procuring raw materials to receiving payment from customers represents a period during which cash is tied up in operations.

This working capital requirement is necessary to sustain the ongoing operations of the business but can also pose challenges, especially if the company faces cash flow constraints or operates with thin profit margins.

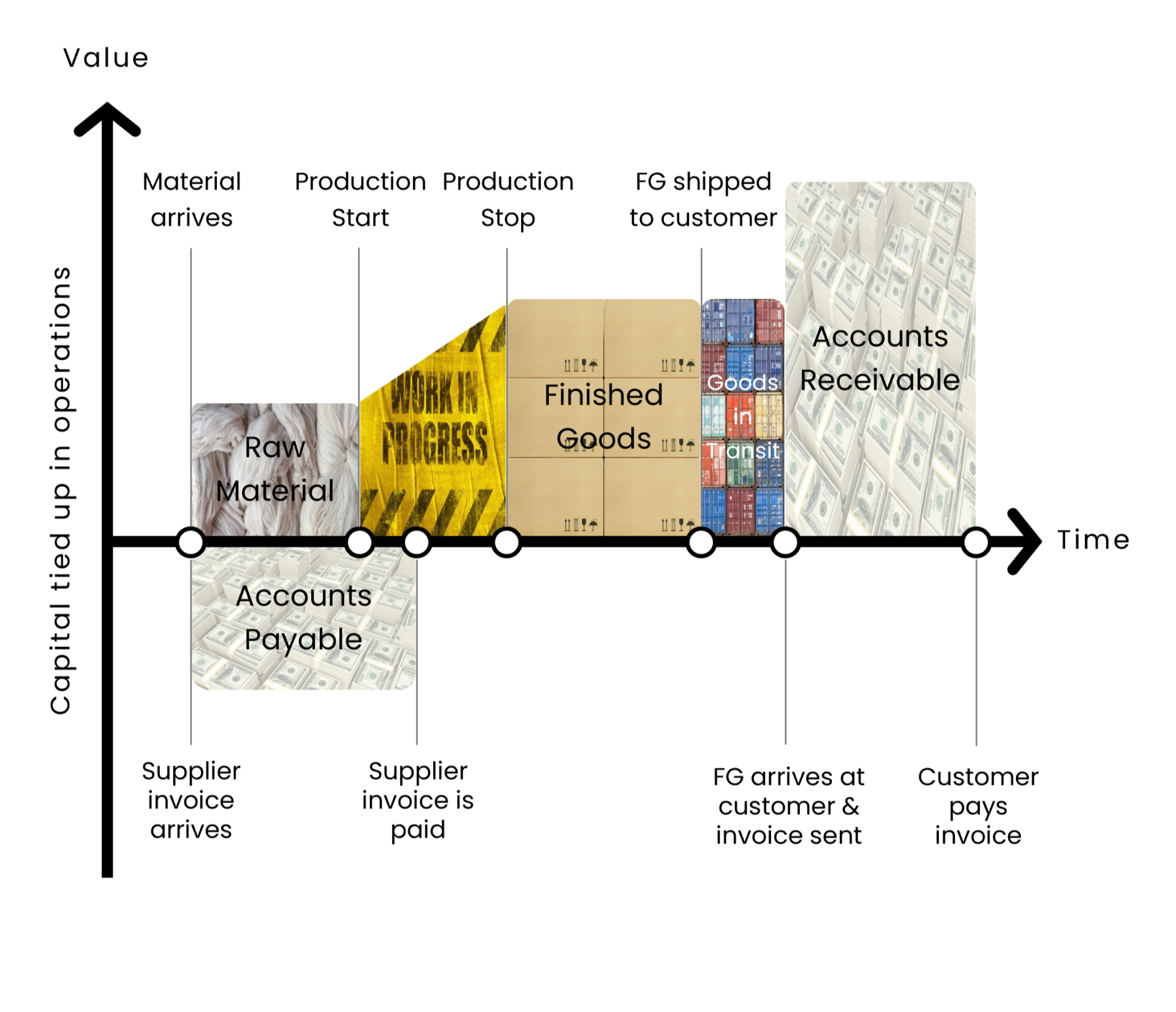

The Cash Conversion Cycle and Time

The Cash Conversion Cycle (CCC) can be understood best as a timeline of cash movements through a company's operations.

It starts when a business buys materials and ends when it finally collects cash from customers. In between, capital flows through different balance sheet accounts - inventory, payables, and receivables - each creating either a delay or a relief in the company's liquidity.

Let us look at this as a timeline with four main events:

- A company Buys material for processing into sellable goods;

- It Pays its suppliers for the material received;

- It Sells products to its customers;

- and finally, It receives Payment for the products sold.

This sequence highlights how Operating Working Capital (OWC) moves through the business and why cash flow timing matters.

To understand these flows, let's look at the key balance sheet accounts one by one and see how they affect cashflow in practice:

1. Inventory Account - Cash Tied in Stock

As soon as materials are purchased and processed, they sit on the inventory account until sold. During this time, cash is essentially frozen in inventory and cannot be used for other purposes.

The length of the arrow, or the time the material is held on the inventory account, depends on how long the material is kept on the shelves before being sold to a customer.

2. Accounts Payable - Supplier Credit as a Source of Cash

When material is bought on credit, the company won't pay until after the agreed supplier credit period reaches its end.

The length of the arrow will reflect the credit time given. Say 30 days as an example.

Until the end of the credit period and payment is made, the value of the material is held on the accounts payable account. It is not until the credit period is over and actual supplier payments are made that cash outflow occurs.

3. Accounts Receivable - Waiting for Customer Payments

When the customer buys on credit, payment is not made until after the credit period has ended. As with account payables, the length of the arrow reflects the credit time given.

When sold and invoiced, a product will leave the inventory account and the corresponding value will move to the accounts receivable, until the credit ends, and payment is made.

It is not until the credit period is over and customer payments are made that cash inflow occurs.

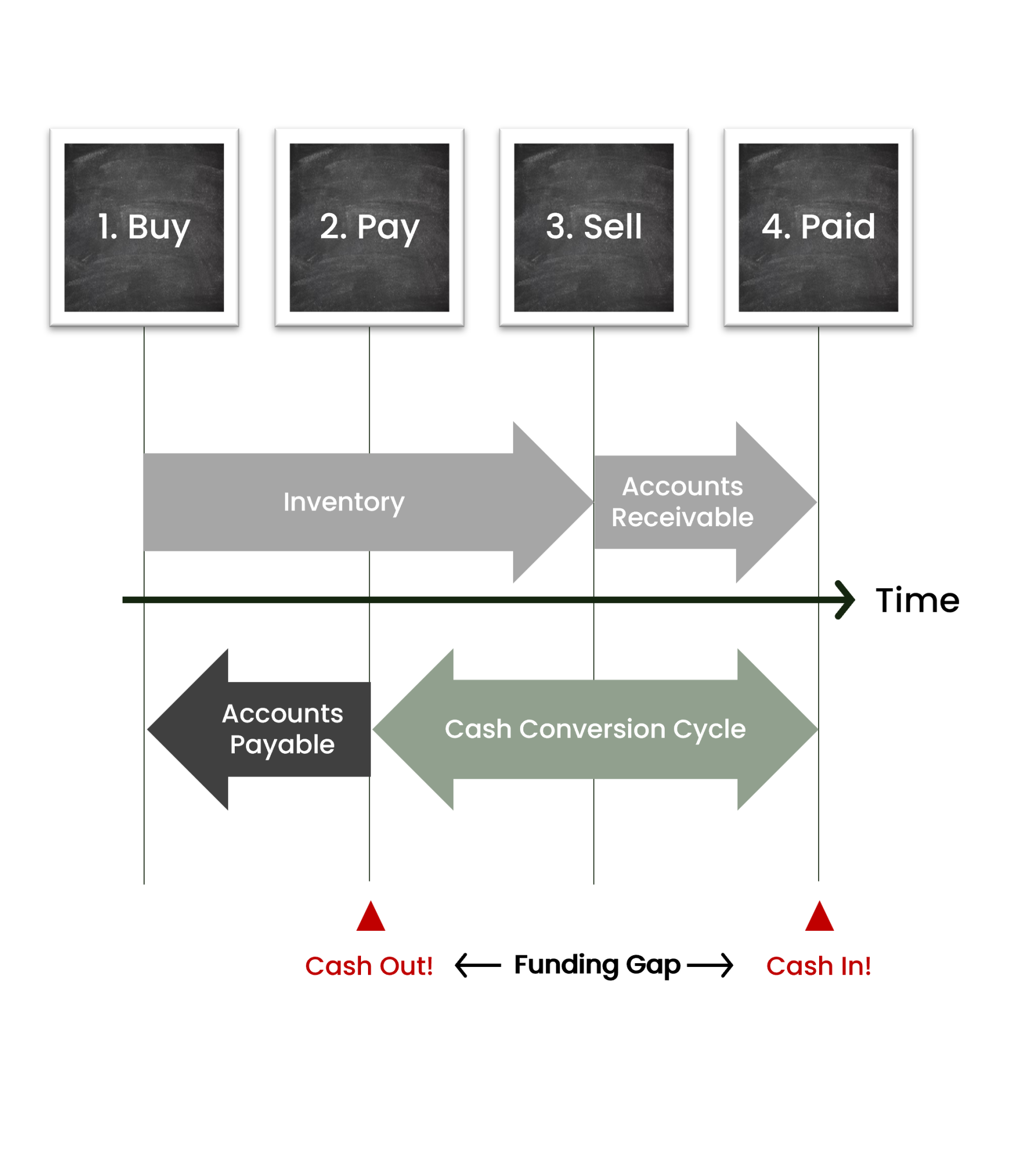

4. The Funding Gap - Measuring the CCC

The total time between paying suppliers and receiving customer payments is the Cash Conversion Cycle. It represents the period during which the company must finance its own operations with internal cash or external funding.

- A short or negative CCC means the business generates cash quickly, reducing financing needs.

- A long CCC means more money is locked in operations, which can strain liquidity.

This is why the CCC is sometimes also called the Funding Gap: it shows how long the business must bridge the gap between cash outflows to suppliers and cash inflows from customers.

How is the Cash Conversion Cycle Calculated?

The CCC encapsulates three key stages of a company's operating cycle:

- The selling of current inventories.

- The collection of cash from current sales.

- The payment to vendors for goods and services purchased.

The CCC is therefore calculated using three other operating working capital metrics:

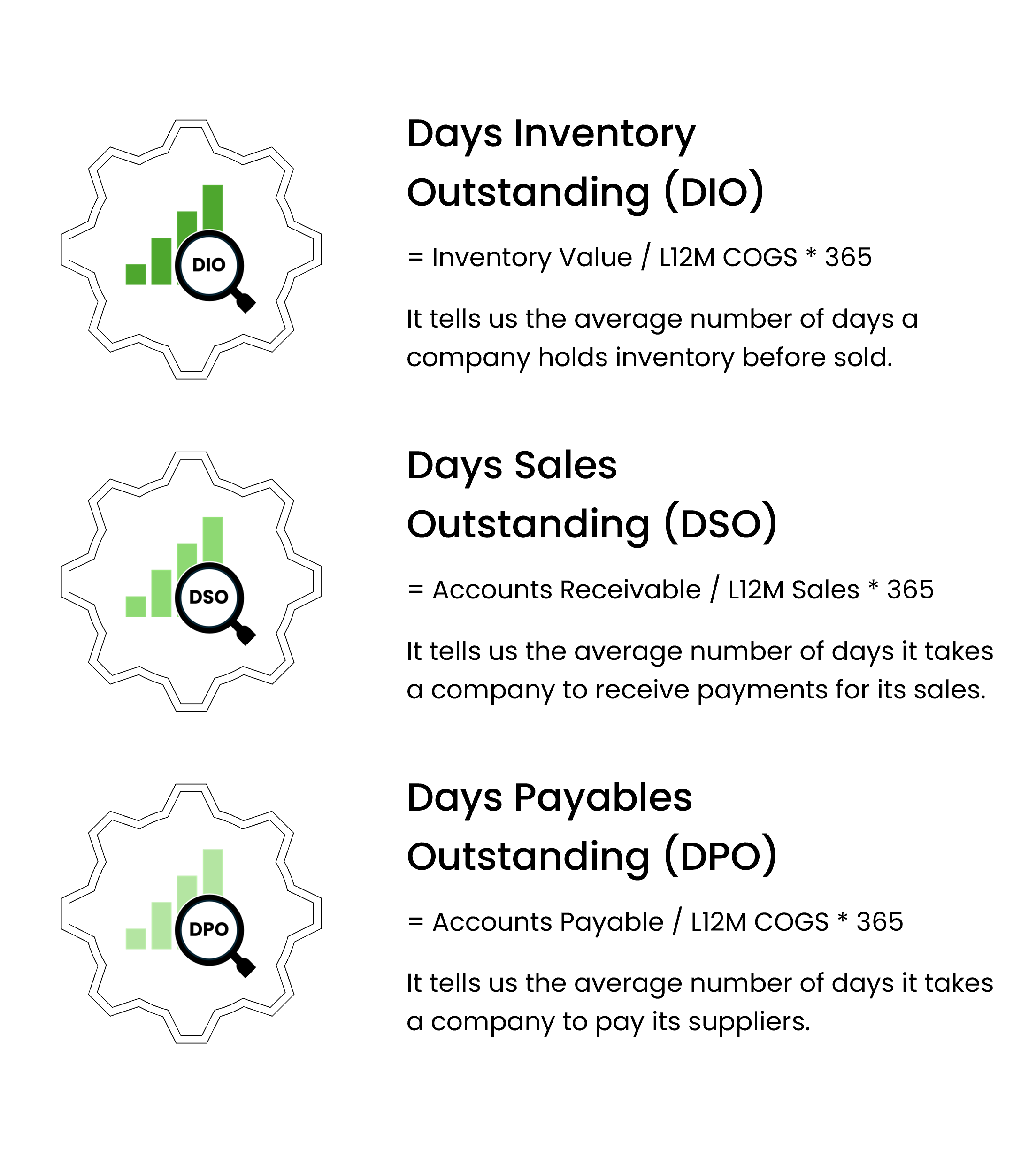

- Days Inventory Outstanding (DIO)

- Days Sales Outstanding (DSO)

- Days Payable Outstanding (DPO)

DIO and DSO are short-term assets, while DPO is classed as a liability.

How to calculate the Cash Conversion Cycle

CCC = Days Inventory Outstanding (DIO) + Days Sales Outstanding (DSO) - Days Payable Outstanding (DPO)

Where:

DIO = Inventory / Annual cost of goods sold (COGS) x 365

The Days Inventory Outstanding metric is a measure of how many days on average a company holds inventory before sold.

DSO = Accounts Receivable / Annual Sales x 365

The Days Sale Outstanding metric is a measure of how many days on average a company takes to receive payments for its sales.

DPO = Accounts Payable / Annual COGS x 365

The Days Payable Outstanding metric is a measure of how many days on average it takes a company to pay its suppliers.

Empty space, drag to resize

Become a Certified Working Capital Practitioner

Check out our eLearning course Managing Working Capital

Interpreting the Cash Conversion Cycle

The Cash Conversion Cycle is a lens into how efficiently a company manages its operating working capital (OWC). It tells you how many days cash is tied up in receivables and inventory, offset by the credit received from suppliers.

The rule of thumb:

- Shorter CCC = faster conversion of invested capital into cash, more liquidity and flexibility.

- Longer CCC = more cash locked in operations, less available for growth or debt repayment.

Why There Is No Single "Good" Level of CCC

There is no universal definition of a "good" or "bad" CCC.

The Cash Conversion Cycle must always be interpreted in context. A short CCC might indicate efficiency in one sector or company but could be impossible - or even harmful - in another. Here's why:

1. Different Industry Dynamics - External Realities

- Different industries operate with very different CCCs.

- Retailers often have short or even negative cycles because they receive cash before paying suppliers, while manufacturers may face long cycles due to production lead times and large inventories.

- These structural realities are beyond management's control, so CCC performance should always be judged against sector peers.

2. Different Business Model - Strategic Choices

- Companies in the same industry can still show very different CCCs depending on their business model.

- For example, subscription-based firms often collect upfront payments, while others extend credit to win customers.

- Such choices reflect strategy - whether the company prioritizes growth, cash discipline, or customer acquisition - and directly shape working capital needs.

3. Different Supply Chain Setup - Design and Trade-Offs

- Supply chain design also plays a critical role.

- Global sourcing and long lead times typically require higher inventory, while nearshoring may reduce inventory but raise costs.

- Negotiated payment terms with suppliers and customers also affect CCC.

These choices sit between external constraints and internal strategy, reflecting trade-offs between liquidity, service, and efficiency.

A company's CCC only makes sense when viewed through its industry, business model, and supply chain context. What is efficient for one may be unsustainable for another.

How to Use the Cash Conversion Cycle (CCC) Effectively

The CCC is not just a financial ratio - it's a practical management tool that can highlight risks, reveal hidden inefficiencies, and guide decision-making.

To make it actionable, companies should focus on following areas:

- Evaluate each component (DIO, DSO, DPO) against their optimal operating working capital Setpoint. The CCC isn't just about shorter being better. Each component must be calibrated to its optimal level - enough to support smooth operations, but not so much that cash is unnecessarily tied up. Without this reference point, companies risk drawing the wrong conclusions from their operating working capital performance.

- Track CCC Trends Over Time. A single CCC datapoint doesn't tell the full story. Make CCC and its components (DIO, DSO, DPO) part of monthly dashboards. Review changes jointly with finance and operations to identify root causes and corrective measures early. Linking CCC trends to operational events can turn raw numbers into actionable insights.

- Benchmark against peers (cautiously). Comparing against peers is useful, but must account for differences in markets, product mix, and strategy. Treat benchmarking as a diagnostic tool rather than a target in itself. Use it to spark discussions about why differences exist and whether they reflect strategic choices, market realities, or operational gaps. Always combine external benchmarks with internal trend analysis to set realistic and sustainable goals.

- Use CCC to Drive Cross-Functional Alignment. The Cash Conversion Cycle (CCC) is influenced by decisions across finance, sales, supply chain, and procurement. When these functions optimize in isolation, they can unintentionally stretch the cycle and weaken liquidity. Introducing shared KPIs such as "Cash-to-Cash Days" and reviewing them in cross-functional forums (e.g., S&OP or working capital councils) helps ensure that trade-offs are managed holistically and support the company's overall cash position.

- Combine CCC with Transaction-Level Data. Ratios like DSO, DIO, and DPO highlight trends, but they don't reveal causes. Transaction-level data - late invoices, disputes, overdue accounts, or slow-moving stock - shows where cash really gets stuck. A stable DSO, for instance, can hide growing overdue receivables offset by upfront sales. "Healthy" inventory days may conceal obsolete stock tying up capital. To get the full picture, link CCC trends with data from O2C, P2P, and F2F processes. This connects financial ratios to operational performance, enabling root-cause analysis and targeted fixes.

Key Takeaway

The CCC is not just a number - it's a strategic indicator of how well profits are being converted into usable cash. By understanding what drives CCC, companies can identify whether liquidity challenges stem from receivables, payables, or inventory management - and act where it matters most.

10 Ways to Improve the Cash Conversion Cycle

Effective management of working capital is crucial for ensuring the smooth functioning of operations and maintaining financial stability.

Strategies such as optimizing inventory levels, negotiating favorable payment terms with suppliers, improving accounts receivable collection processes, and efficient production scheduling can all help minimize the amount of cash tied up in operations and improve overall liquidity.

Strategies to reduce a company’s cash conversion cycle could include:.

1. Optimize Inventory Management:

- Keep inventory levels optimized to prevent overstocking or stockouts.

- Align system applied target inventory and safety stock requirements to demand profile and required service levels.

- Implement demand-driven or just-in-time inventory systems to reduce excess inventory holding costs.

- Actively work to reduce slow-moving or obsolete inventories, as these can take up space at the expense of in-demand high runners.

2. Streamline Customer Invoicing and Collection:

- Accelerate the collection of accounts receivable by sending correct and timely invoices and following up promptly on overdue accounts.

- Implement pre-dunning for habitual late payers. Actively work to reduce dispute resolution time.

- Also, consider implementing stricter credit policies to reduce the risk of late payments or defaults.

3. Manage Supplier Invoice Receipt and Payments:

- Ensure swift and accurate goods receipt and system entry practices.

- Make sure applied payment terms are aligned with supplier agreements.

- Pay on time but also identify and avoid payments made earlier than the due date.

- Also, for invoices due on a weekend, consider making the payment the following Monday rather than the Friday before, as no transfers will take place over the weekend anyways.

4. Improve Operational Efficiency:

- Streamline workflows, invest in technology, and train all staff to work more effectively.

- Enhance operational efficiency to reduce waste, re-work as well as internal lead-times. Identify and remove bottlenecks.

- Ensure frozen production plans to maintain optimal sequencing. Shorten change-over and ramp up time.

5. Improve Sales Efficiency:

- Actively work towards favorable payment terms as part of all customer negotiations.

- Assist collection in cases of disputes or habitual late payers.

- Improve forecast accuracy and align demand and supply through active participation in Sales and Operations Planning processes.

- Align forecasts with relevant planning horizons, and make sure they are presented in a format relevant for operations (in same unit as used for planning purposes).

6. Improve Purchasing Efficiency:

- Actively work towards favorable payment terms as part of all supplier negotiations.

- Also, weigh in implications of longer delivery lead times when selecting suppliers: understand the implications on inventory and cost of capital.

- Review current supplier agreements and identify suppliers with terms shorter than policies allow.

- Ensure only approved suppliers are used and align service level agreements across the organization.

- Reduce complexity by consolidating the number of suppliers or purchased items to improve both terms and cost.

7. Monitor Working Capital & Cashflow:

- Monitor key working capital metrics and ratios to identify areas for improvement and track progress over time.

- Include relevant leading metrics to allow for early recognition of inefficiencies.

- Install working capital reporting and follow-up in relevant management meetings as a fixed agenda point. Assign ownership and accountabilities.

8. Set & Align targets Across Functions:

- Ensure relevant and achievable targets, aligned with the company's optimal working capital levels.

- Balance targets across functions to avoid conflicting agendas, and local optimization at the expense of the total business.

- Ensure working capital and cash are high on the management's agenda and connected to relevant incentive structures.

9. Utilize Working Capital Financing:

- Explore various working capital financing options such as Supply Chan Financing (e.g., Receivables Financing, Approved Payables Financing, etc.).

- Ensure to evaluate the cost-effectiveness of financing options.

10. Regularly Review and Adjust Strategies:

- Continuously monitor your working capital management practices and adjust them as needed based on changes in market conditions, business performance, or other factors impacting liquidity.

By implementing the above strategies, a company will improve its working capital and strengthen its financial position, ultimately enhancing its ability to meet short-term obligations and support long-term growth.

However, it is important to recognize that a company's cash conversion cycle cannot be viewed in isolation; it also reflects the interactions with suppliers and customers.

For example, when a company extends or delays payments to its suppliers, this will negatively affect the supplier's cash conversion cycle by increasing their DSO.

This could, in turn, create cash flow challenges for the supplier, potentially leading to future price increases or impacting on their ability to meet orders on time and in full.

Conclusion

The Cash Conversion Cycle is more than an accounting metric - it is a window into how effectively a company turns operating working capital into cash.

A short or well-managed cycle strengthens liquidity, reduces financing needs, and frees up capital for growth.

A poorly managed cycle, on the other hand, can quietly erode financial flexibility even when profits look healthy.

Success lies in managing CCC holistically: aligning functions, tracking trends, and connecting high-level ratios to operational realities. Companies that actively measure, understand, and improve their CCC gain not only stronger cash flow but also a lasting competitive edge.

Take Your Next Step: Become a Certified Working Capital Expert with Working Capital Hub’s Accredited Online Courses

Subscribe to our newsletter

Thank you!

Policy Pages

Copyright © 2025